How Steel Gets Its Strength (and Other Mechanical Properties)

Steel is known for its strength, but what exactly makes it strong?

To understand how steel achieves its strength, we need to explore the science behind its composition, treatment, and processing. This article will focus primarily on coil/sheet steels (<3mm) that are produced at scale, excluding stainless steel grades for simplicity. While stainless steels share many of the same strengthening mechanisms, such as grain refinement and alloying, they aren’t the focus here. Additionally, ASTM or EN standards will be referenced, particularly as some steel grades aren’t manufactured in Australia or New Zealand. We will also exclude topics such as thickness/size effects and Young’s modulus (stiffness), which will be explored in future articles.

Trade-offs in Steel Strength

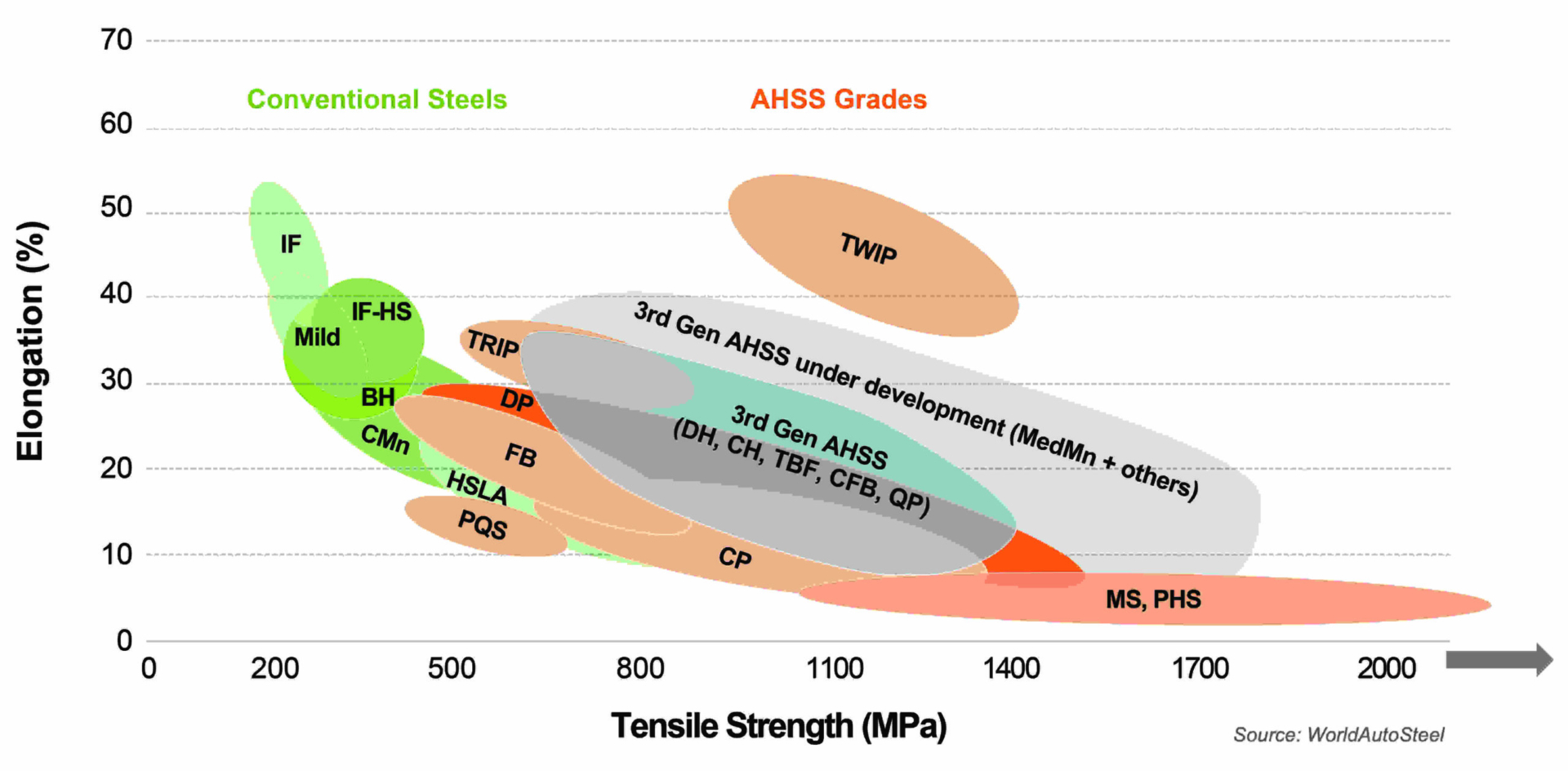

Enhancing steel’s strength often involves trade-offs. As strength increases, elongation typically decreases, which can reduce formability. Introducing alloying elements to boost strength and maintain ductility may adversely affect weldability and increase hardness. Additionally, the yield ratio – the ratio of yield strength to tensile strength – is a critical factor; a higher yield ratio indicates less capacity for plastic deformation before failure, making the steel more brittle.

Why Stronger Isn’t Always Better

Higher strength doesn’t necessarily mean higher quality. Steel grades are engineered with specific applications in mind, balancing both performance and cost. For example, a Hollow Structural Section (HSS) grade like C450 is relatively basic and economical in both composition and processing – despite its high yield strength. In contrast, an ultra-low carbon Interstitial-Free (IF) or Extra Deep Drawing (EDD) steel may have a much lower yield strength (e.g. ~150 MPa) but require tighter chemistry control and advanced processing to enable very high formability, increasing production costs. Although there are thousands of steel grades and overlapping standards, the ways steel achieves its strength and mechanical properties typically fall into three key categories, discussed below.

1. Work Hardening (Strain Hardening)

When steel is deformed through processes like rolling or drawing, its internal structure becomes more resistant to further deformation. This happens because the dislocation density increases – dislocations are tiny defects or “slips” in the crystal structure. The more dislocations there are, the harder it is for the atoms to move, which increases the steel’s strength.

2. Alloying

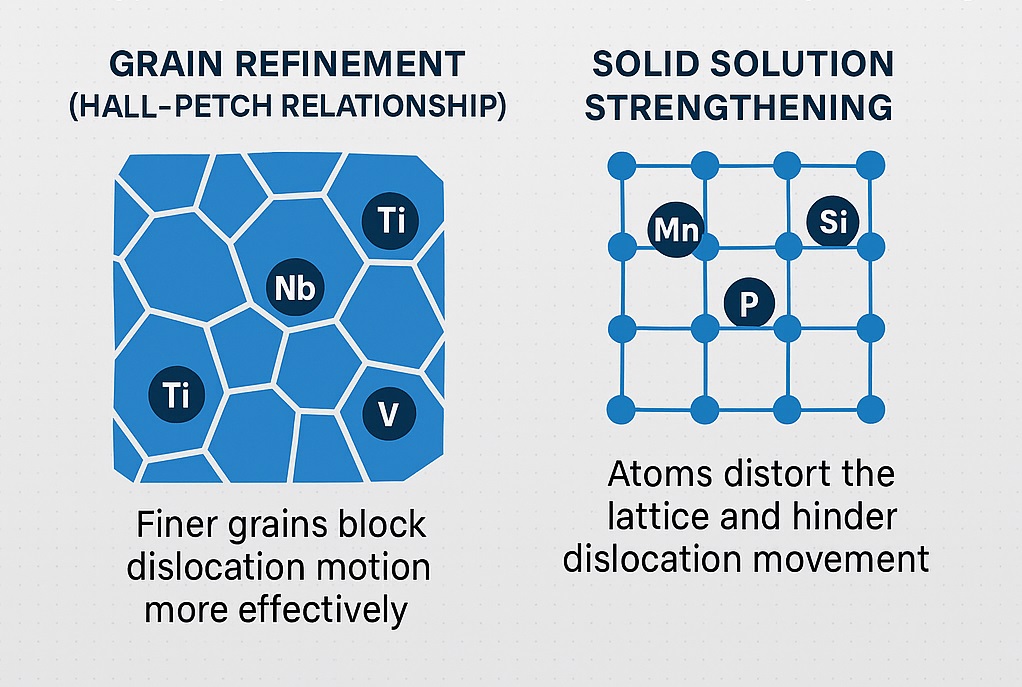

Adding elements such as carbon, manganese, chromium, or nickel improves the strength and performance of steel by changing its internal structure. One important effect is solid solution strengthening, where these added elements mix into the steel and slightly distort its crystal pattern. This distortion makes it harder for the layers of metal to move past each other, which increases strength and hardness. Alloying can also help form useful microstructures and improve properties like toughness, corrosion resistance, and the steel’s ability to be heat treated.

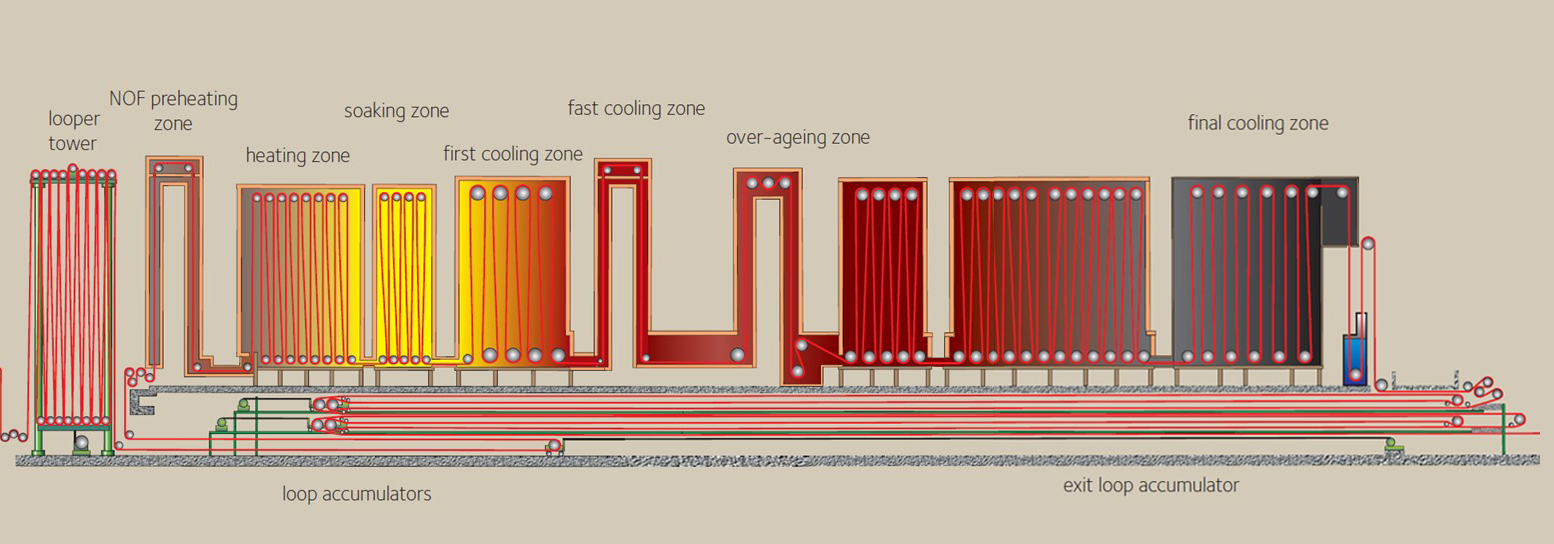

3. Heat Treatment

Processes like annealing (continuous and batch), quenching and tempering and thermomechanical processing (TMCP) change the steel’s microstructure. These changes adjust properties like strength, hardness, and ductility by altering the arrangement of phases (e.g., ferrite, martensite, bainite) within the steel. Some treatments also refine the grain size, which increases strength by creating more grain boundaries that resist deformation.

While these three strengthening methods are often discussed separately, they frequently overlap in real-world steel production. As such, the remainder of this article won’t be strictly divided by these categories but will instead follow a progression based on increasing strength.

Mild Steel

To start, we’ll focus on low-carbon mild steel (typically containing less than 0.25% carbon by weight), where work hardening plays a central role in increasing strength. In the absence of alloying elements that enable heat treatment and/or contribute to solid solution strengthening, mild steel generally has a yield strength ceiling of ~500 MPa. Because of its simple composition and limited response to heat treatment, work hardening is often the primary method used to enhance its strength, particularly in cold-rolled processing.

Work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is often considered the simplest of the three main methods for strengthening steel. Unlike alloying or heat treatment, which require changes in chemical composition or precise temperature control, work hardening increases the dislocation density within the steel through plastic deformation. This makes the material harder and stronger but also less ductile. While the process itself is relatively straightforward, its effects on the material’s mechanical behaviour – particularly the balance between strength and formability – can be complex.

At Industrial Tube Manufacturing, we worked with a customer on a medical durable product that required a tube with higher yield strength to withstand cyclic loading and improve fatigue resistance. The product featured a telescoping insert, so a Precision Tube with tight dimensional tolerances – particularly low thickness variability in the base strip – was essential.